“I had a computer and internet connection, and that was enough for me,” he said.

He also had ideas — ideas to one day conduct ground-breaking research for industries right here on campus.

Such research would be a win-win: it would benefit students by giving them practical experience that would prepare them for lucrative careers, and would quench Petrovic’s thirst for using science to positively impact the world.

He needed funding, and he needed a lab.

In the years that followed, he got both. And his research, in collaboration with his colleagues, has enabled worldwide companies to use sustainable processes and materials for commercial products.

This summer, Petrovic also earned a prestigious recognition: a top global ranking by Research Gate as a leading scientist whose research has been cited by other scientists an astounding 13,757 times.

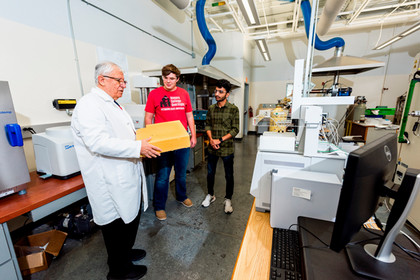

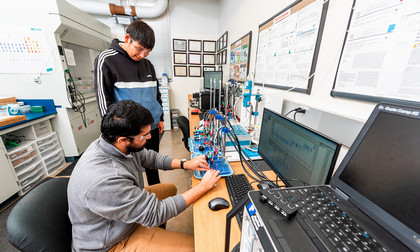

The labs in which he once worked evolved into what today is known as the state-of-the-art National Institute for Materials Advancement. Occupying 22,000 square feet, NIMA is comprised of 18 labs, 22 fume hoods, and resources Petrovic couldn’t have dreamed of in 1994.

Petrovic, who still maintains an office there, recently celebrated his 84th birthday.

“I love it. I don’t know what else I would do if I wasn’t here,” he said. “Plus, I have so much experience, I can help the people here.”

“Everything around us uses polymers — plastics, foams, fabrics — it’s part of our world,” he said. “My interest has always been in making it better.”

Petrovic grew up in a small town in Yugoslavia (now Serbia) and had excellent chemistry teachers.

“Then I found a guy who advised me to go into chemical technology,” he said. “I switched, and it was the best decision I ever made. This is a science about how to make things.”

Drawn to fiber science in particular, his work at first focused on synthetic fibers known for their elasticity — Spandex and Lycra — made from polymers. The process was invented when Petrovic was a teen, and as his education and career progressed, so did the world of fiber science.

He earned degrees in Belgrade and Scotland, then taught in Serbia and conducted research at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst before coming to Pittsburg.

Here, Petrovic kicked off research at the university’s fledgling research center with a $30,000 grant to cast compounds from castor oil for an agricultural organization, followed quickly by landing a contract with Titleist to work on gels for golf shoes.

His labs and staff expanded, they employed undergraduate and graduate students to help with the volume of work, and by 1998, two of their materials were featured in Golf Digest in the category of best improvements in golf technology.

Petrovic expanded his work to teach in the Chemistry Department and launched the first course in the U.S. that featured polyurethanes as a regular part of the curriculum.

In 2007, he and his team moved to the newly finished Tyler Research Center, home to the Kansas Polymer Research Center, at the east edge of campus. There, they took their research to turn raw agricultural materials into polymers to the next level, years before the terms “sustainability,” and “renewability” were part of our everyday vocabulary.

“Suddenly, the world’s largest companies were coming to a small town called Pittsburg offering cooperation,” he recalled.

His team landed major contracts with United Soybean, the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Cargill, BF Goodrich, and Honeywell.

Usually, fewer than 2 percent of patents are commercialized.

“We should be proud to have almost half of our patents commercialized,” he said. “This would not be done without good people.”

At the KPRC, which a few years ago rebranded to NIMA and is now directed by Tim Dawsey, PhD, there have been many good people — brilliant chemists and collaborators who came here from Yugoslavia, Romania, India, China, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Serbia, and the U.S.

Their contributions have created a premier research institution in the field of conversion of natural products to polymers.

“This today looks surreal — unexpected in a small town and at a small university,” Petrovic said.

In total, he has published three textbooks on polymers, 17 book chapters, and more than 500 publications and conference presentations, as well as 25 patents.

And, he said, “I’m not done yet.”

Last October, three faculty in the Pitt State Chemistry Department were recognized as being on a list of the world’s top 2 percent of scientists, a list produced by Stanford: Professor Ram Gupta, Assistant Professor Mazeyar Parvinzadeh Gashti, and Assistant Professor Alessandro F. Martins.

The ranking is produced annually and takes into account the scientific achievements of researchers in a broad range of fields. The annual list draws from a variety of metrics and serves as a powerful tool for identifying global scientific leaders.

Gupta also was named to the list in 2022.

The university earned a Research Activity Designation from the Carnegie Foundation in 2025 for its investment in advancing science and discovery through research across the disciplines of engineering, life sciences, social sciences, and physical sciences.

The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education is the leading national framework for recognizing and describing the contributions of postsecondary institutions.